LEOS CARAX

"The cinema is an anti-universe where reality is born out of a sum of unrealities."

— Jean Epstein

I’m writing this in hopes that all who have never watched Les Amants du Pont Neuf, aka The Lovers on the Bridge will do themselves the favor of partaking in this feast for the senses.

Leos Carax is a poet of the cinema, and Les Amants du Pont Neuf, his triumph. There are several reasons why you may not have heard of Carax and his films. His unique poetic expressionism informs an unusual mix of documentary, reality and fantasy that breaks all the rules American cinema usually plays by. Known as l’enfant sauvage of the French cinema, Carax entered my radar by way of cinematographer Jean-Yves Escoffier, who was the partner of a friend in the mid-1990’s. Seeing Les Amants du Pont Neuf for the first time, I felt a type of elevated delirium at having witnessed just how brilliant an art form film can be. And Denis Lavant’s face. To see someone on film who felt so real, so un-pretty like the wild boys of my No New York was a revelation in itself. Lavant plays the drunken street punk Alex, who in the film’s first scene collapses into the street where his leg is run over by a car. He’s thrown into a Parisian drunk tank – Jean-Yves related to me how the scenes in the tank were filmed verité, utterly and distressingly real – and after his release, makes his way to his new home on the Pont-Neuf, which is under construction. I won’t go further into the details of this story other than to say it’s about vision and love’s delirium, and to describe a moment in the film where everything comes together in a symphony of ecstatic action and emotion. Watching this moment gave me a sensation I will never forget, a Stendahl syndrome. The dance of bodies, birds, machines and planes, the juxtaposition of images and direction of the movements in the cuts, and then the sound, dropping out to silence at just the right instant – it’s a montage that literally took my breath away and stays with me as the highest in art to forever strive toward.

In Les Amants, Leos Carax does what only certain poets (like Rimbaud) have accomplished before him – he elevates squalor into the mystic. The love between Alex and Anna is street love, dirty love, symbolic of the messiness of the cleanest of bodies and hearts in love and way too unhygienic for American critics who tend to shun the poetic in film. America’s filmmaking machinery opts for hard and fast boundaries between realism, fantasy and beyond. You rarely find sublime hybrids in our commercial cinema because America loves its boundaries. Yet in art, as in sex, boundaries exist only to be trampled on (in the latter, with permission of course).

Carax approaches film first as poetry, then as a dance. The city, as character, dances along. He’s not afraid to show us raw libido without the taint of porn (as in the mini-porn flick tucked inside Blue is the Warmest Color). In Les Amants we see and hear the separate musics of lovers dancing in the geography of ecstasy that is Paris as holy whore. The lovers come together with songs overlapping, the action and sound rising to climactic mash-ups of sensual intoxication. The exuberance and utter abandon of the actors’ movements in Carax films is Cartesian, in that it mixes fantasy with the life of the mind as it relates to the body. In Passions of the Soul, Descartes talks about animal spirits produced in the blood, responsible for the physical stimulation that causes a body to move. In Denis Lavant’s Alex, we see his animating blood-creatures showing off for Binoche’s Anna in a feast for the eyes – pure Duende in full throttle.

— Jean Epstein

I’m writing this in hopes that all who have never watched Les Amants du Pont Neuf, aka The Lovers on the Bridge will do themselves the favor of partaking in this feast for the senses.

Leos Carax is a poet of the cinema, and Les Amants du Pont Neuf, his triumph. There are several reasons why you may not have heard of Carax and his films. His unique poetic expressionism informs an unusual mix of documentary, reality and fantasy that breaks all the rules American cinema usually plays by. Known as l’enfant sauvage of the French cinema, Carax entered my radar by way of cinematographer Jean-Yves Escoffier, who was the partner of a friend in the mid-1990’s. Seeing Les Amants du Pont Neuf for the first time, I felt a type of elevated delirium at having witnessed just how brilliant an art form film can be. And Denis Lavant’s face. To see someone on film who felt so real, so un-pretty like the wild boys of my No New York was a revelation in itself. Lavant plays the drunken street punk Alex, who in the film’s first scene collapses into the street where his leg is run over by a car. He’s thrown into a Parisian drunk tank – Jean-Yves related to me how the scenes in the tank were filmed verité, utterly and distressingly real – and after his release, makes his way to his new home on the Pont-Neuf, which is under construction. I won’t go further into the details of this story other than to say it’s about vision and love’s delirium, and to describe a moment in the film where everything comes together in a symphony of ecstatic action and emotion. Watching this moment gave me a sensation I will never forget, a Stendahl syndrome. The dance of bodies, birds, machines and planes, the juxtaposition of images and direction of the movements in the cuts, and then the sound, dropping out to silence at just the right instant – it’s a montage that literally took my breath away and stays with me as the highest in art to forever strive toward.

In Les Amants, Leos Carax does what only certain poets (like Rimbaud) have accomplished before him – he elevates squalor into the mystic. The love between Alex and Anna is street love, dirty love, symbolic of the messiness of the cleanest of bodies and hearts in love and way too unhygienic for American critics who tend to shun the poetic in film. America’s filmmaking machinery opts for hard and fast boundaries between realism, fantasy and beyond. You rarely find sublime hybrids in our commercial cinema because America loves its boundaries. Yet in art, as in sex, boundaries exist only to be trampled on (in the latter, with permission of course).

Carax approaches film first as poetry, then as a dance. The city, as character, dances along. He’s not afraid to show us raw libido without the taint of porn (as in the mini-porn flick tucked inside Blue is the Warmest Color). In Les Amants we see and hear the separate musics of lovers dancing in the geography of ecstasy that is Paris as holy whore. The lovers come together with songs overlapping, the action and sound rising to climactic mash-ups of sensual intoxication. The exuberance and utter abandon of the actors’ movements in Carax films is Cartesian, in that it mixes fantasy with the life of the mind as it relates to the body. In Passions of the Soul, Descartes talks about animal spirits produced in the blood, responsible for the physical stimulation that causes a body to move. In Denis Lavant’s Alex, we see his animating blood-creatures showing off for Binoche’s Anna in a feast for the eyes – pure Duende in full throttle.

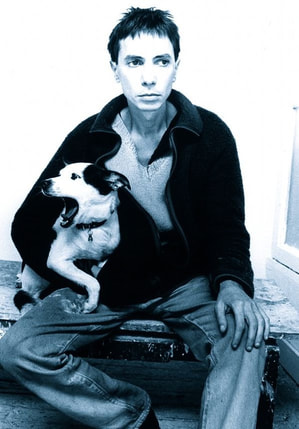

Denis Lavant

Denis Lavant

Another word about Denis Lavant – he plays the lead in all but one of Carax’s films, usually as the character of Alex, which is Leos Carax’s birth name as well as his alter ego. (This recalls the poetic relationship of Francois Truffaut to his character and alter, Antoine Doinel, always played by the actor Jeanne-Pierre Léaud.) When both men were younger, Lavant was a doppleganger for Carax. Another reason why Carax films live so far beneath American radar – people here would consider Denis Lavant downright ugly, and we don’t want our cinema idols to be anything but glamorously attractive. Attractive to our skewed aristocracy of beauty, that is. The French phrase for Lavante would be belle laide, or jolie laide – beautiful ugly— and that he is, exquisitely so. And just as jolie laide is an alternative type of beauty, Les Amants is all about the way we choose to see. The cruelty of love, of Alex preferring that Anna stay blinded rather than have her possibly see him, and their life together on the bridge, clearly enough to flee it, resolves at the end of the film when she does, in fact, see clearly. That’s the only spoiler I’ll reveal, aside from saying James Cameron stole Carax’s iconic shot of Alex and Anna on the prow of the barge for his Titanic. But then again, didn’t Carax pinch it from Jean Vigo? Jean Genet said that one interpretation of genius could be the ability to commit clever thievery.