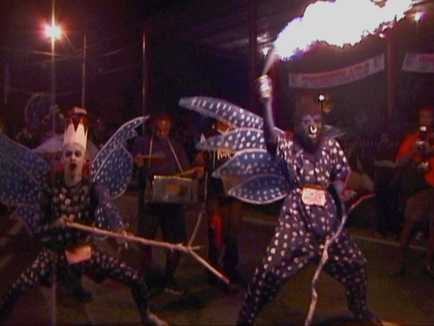

Curtis Blackman, the Dragonman

Curtis Blackman, the Dragonman

A Spy in the House of Mas

Mas = masquerade, or Carnival

an abridged version of a piece published in

the Trinidad Guardian, February 19, 2006

by Adele Bertei

Sailor 'Mas', 1960s

Sailor 'Mas', 1960s

In the States, politics and culture make for strange bedfellows. Although we’ve gifted the world with our music—a rich language evolving from African rhythms dancing with European melody traditions—we remain a segregated nation still wrestling with the malignancy of racism. Our overriding cultural incentives to create are predominately attached to the creation of cash. The U.S. government has stripped public schools of their art programs, and the population is overall too racially disparate, classist and xenophobic to come together for all-inclusive communal celebrations. We are divided, conquered, and if we’re lucky, working—and working way too many hours motivated by the socially-engineered desire to consume all we need to be ‘happy’. This need is so acute that when we can’t afford to feed it by the sweat of our labor, we resort to crime, or the escape from oppression drugs can provide, which explains why 30 percent of all African American men between the ages of 20 and 35 in the U.S. are incarcerated. The diabolical shadows of systemic racism and lack nof education across color lines makes a gargantuan task out of securing decent housin, feeding and clothing your family, and keeping them safe and healthy. Our lack of a meaningful culture that brings people together, as opposed to dividing us, makes us poorer in spirit and pocket while corporations grow obese off the sweat of our labor and their insatiable greed. If you are not a wealthy American (and this country is all about generational wealth) you’d best lie back in a passive sleepwalk while the soucouyant of consumerism sucks the spirit from you.

I met my first Trini in the mid-nineteen eighties, when I knew nothing of the twin islands. Aside from Jamaica’s reggae music, and Mustique as a rich rock star’s paradise, for all I knew the Antilles could have matched what V. S. Naipaul once described so disparagingly: “History is built around achievement and creation; and nothing was created in the West Indies”. Strange, and terribly wrong, coming from a Trini native who wrote so movingly about the country in several of his books. I would discover that nothing could be farther from the truth; obscurity and insignificance does not, by any means, equate a lack of achievement. I’ve come to believe obscurity is the island’s greatest blessing.

When I first discovered After discovering Trinidad as kaleidoscopic in art and pleasure of life, I was shocked at how the rest of the world could be ignorant to all it has to offer. Mistakenly, I expected more ambition from its artists and craftspeople, its musicians and storytellers—why were they not helping the world understand just how incredible is the cultural phenomenon of the music and the Mas? I was wrong in this, in wanting something it could not give. As if all it offered wasn’t enough. I began documenting Carnival in the year 2000, and at the time, a young cameraman from Utah was traveling with us. We took him into Sea Lots, a seaside shantytown to film one of our main subjects, Curtis Blackman, who lives in what most would call a shack. Curtis showed us his handiwork; the home he had built with his own hands, and the costumes he so lovingly assembles with every penny he makes, year after year. When we walked through Sea Lots with Curtis, everyone knew and greeted him warmly as ‘Dragonman’.

Adorned in his papier maché Dragon head, Curtis danced in the street. I watched and understood the happiness Curtis felt was directly related to the support he receives from his community for his creativity and imagination. Penniless Curtis was free, and richer than most. Free to fully express his creativity through the Mas, which is for many, a year-long process which infiltrates every part of daily life in one way or another. Later that evening, the Utah cameraman expressed his compassion over the poverty in Sea Lots and what he thought was Curtis’s life of misery. “That poor poor man. It really shows you how lucky we are in the states.”, said Utah, shaking his head in a gesture of extreme pity. This was a defining moment in my experience and understanding of Trinidad, and of creativity. In no mood for confrontation with Utah, I walked outside, preferring to listen to the bark of native frogs and to reflect on how impoverished we are in America. Deluded, hypnotozed by social media, disconnected from our imaginations, from spirit, and from one another. And how blessed is Curtis Blackman.

The worst thing you can offer an abandoned child who has grown up rough is pity, for shame is deeply humiliating. The best you can offer is a respectful recognition, maybe some admiration for the tenacity of spirit it took that child to survive. Just as the idea of art as belonging to every citizen is the essence of Trinidad’s cultural nature, a gleaming survival is the essence of its history, its present, and its future. This survival shines as hard and as bright as a diamond, and for those of us lucky enough to recognize it glittering beneath the haze of ‘third world’ stigma, the view is endlessly astonishing. Speaking about Trinidad’s seemingly disparate mélange of citizens and its colonial history, Derek Walcott said it best: “Break a vase, and the love that reassembles the fragments is stronger than that love which took its symmetry for granted when it was whole.”

I saw this love everywhere when I began to truly see and feel the country. I saw and heard it in the voice and eyes of Brother Resistance as he recited the lyrics of his rapso song “The Glory of Kings”, in the laughter and schtyups of Rachel Price, in the picong of Nikki Crosby and Errol Fabian, in the Orisha chants of Ella Andel. I felt it when the people swarmed around Lord Kitchener’s hearse at his passing, mourning his death by celebrating his art as they sang "Sugar Bum". I saw it in the self-satisfied little jigs Clive Bradley would dance as he rehearsed the Witco Desperadoes into goose-bump-inducing crescendos at their Laventille pan yard, and when Machel Montano and Drupatee Ramgoonai sang and danced their duet “Real Unity” to an ecstatic crowd of Indian and African Trinis. I watched it dance like electricity in the classical hand gestures of Shiv Shakti’s choreographer Michael Salikram. I saw it in the way Curtis Blackman carefully sewed shiny fabric over pieces of broken bottle glass, fashioning talons for his dragon costume, and as I sat entranced, listening to Peter Minshall weave his magical story about Washerwoman and ManCrab around me like a cloak of forewarning I’d never want to shake.

When my directing partner and I showed the rough cut of our documentary film (entitled Made in Trinidad) in Los Angeles to an audience of roughly 500 people, they gave it a standing ovation. Yet no film festival would accept it aside from a tiny Black Film Festival in Berlin. Grants for documentaries all rejected our proposals. Public television gave us a polite no thank you. Were they put off by the sequence we shot of jouvert from atop a truck, looking down on thousands upon thousands in a crowd predominantly African, dressed in not much more than mud and fright wigs, winin’ and chippin’ down the street together arm in arm? I can hear the racist wheels turning: Why aren’t they shooting and killing each other? Where’s the riot? How can a whole nation of African and Indian people form such an amazingly creative community based around one yearly event? This does not fit the paradigm, it’s impossible. It can’t be authentic!

We did not intend to make the film to instruct. The film evolved from a childish excitement to share, to say “Hey, look at the treasure we’ve discovered!” But fashion is fashion, and the unspoken shall always remain. Makes me think of a powerful story by Ursula Le Guinn, which poses the question that so much of our happiness is predicated on the suffering of others, and we must believe and uphold that suffering in order to be happy ourselves. The story is called The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas. Yet in the case of Trinidad, there is no child locked up and suffering. That child is dancing, and white entitlement prefers we shut our eyes to its beauty. On my trip back to Trinidad this last Christmas after a four year hiatus, I was shocked to find the front pages of several Trini newspapers shouting out reports of kidnappings, choppings and murders. What’s really going on in Trinidad? Is the current reigning soucoyant of Trinidad not a Trini at all, but in reality, American consumer values sneaking in through television and advertising, pressuring Trini’s to feel like they haven’t enough, that they have to kidnap and kill to get it? When I first came to Trinidad, you did not see hardly an inch of the violence in the press and on TV that now exists. MTV hadn’t yet invaded, glorifying gangstah rap and guns, but that’s all changed. I now see Trini boys with their low-hanging jeans now, mackin’ and posin’. Robbing shops, talking bad-ahss trash. They can play gangstah, yet I know they would never for a minute call their women bitches and ho’s. Try that on Trini women and we’re talking Lysistrata. I will not be so presumptuous as to imagine I understand what is going on politically in T&T, but a nation of brutal murderers is certainly not the country I see.

There is a much larger truth at work here in Trinidad, one the world would rather ignore than discuss or defend—the belief in the creativity of the human spirit and the encouragement to express it, both as an individual, and on a grand, massively cathartic scale. Creativity is the birthright of every citizen, and its encouragement begins from the day you draw breath and lasts ‘til the day you leave the planet. It belongs to heads of corporations and street sweepers in equal measure, knows neither race, class, gender, sexual label, age, or religion. Here it is every human being’s pleasure to play with language, to dance, sing, paint, make music, adorn oneself, share ancestral cultures, arts and beliefs, and act out rituals which make the spirit soar. Everyone is active, everyone is moving, participating as they blend all into a formidably beautiful hybrid that transcends the ordinary and transforms life into an extraordinary circumstance of communion with one another. What happens here in Trinidad is mystical. Call it God or call it science. In a more perfect and just world, I consider the two inseparable.

I’m a spy in the house of Mas, but the disseminators of information in America turn a deaf ear to the pearls I bring back from this island. So I turn around and give it back to the country that informs me, that makes me a better human being. In Trinidad, I’m neither tourist nor native, caught in a netherworld where suitors often find themselves, courting my prospective lover, wondering if she will deign to love me back. And every time I touch down on her shores, the wonder dissolves into joy and my grateful heart breaks open once again.

— Adele Bertei